Introduction

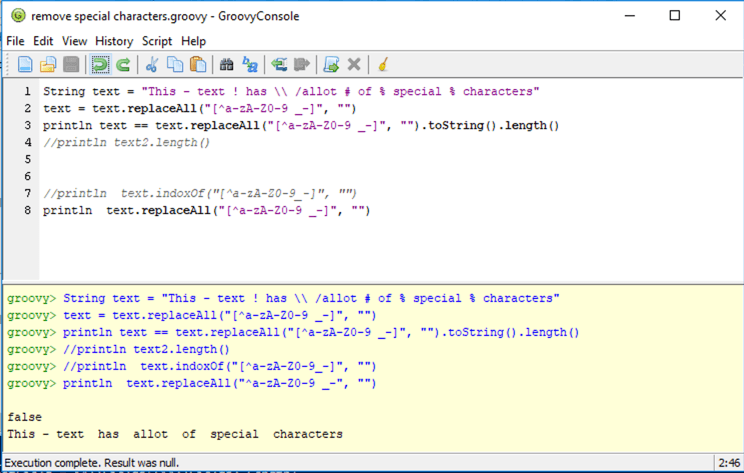

Before we jump in, there are a number of questions you are going to have at the conclusion of this article. Please post comments and I will answer them, but keep in mind, this is an example. Are there different ways to accomplish this? You bet. Should the data sync directly to the rFin database? Probably not, as there are calculations in the fin database that likely need to happen. This could be so complicated that nobody would follow it, so some liberties have been taken to simplify the explanation. The hope is that you can take this, as it has all the pieces required, and modify, add pieces, alter others, and be able to create something that meets your needs. This is a continuation of Part 18. Please read that before you continue.

A Visual

Before moving into the steps of the process, the following diagram is an overview.

Step 1: Validating User Input and Executing Business Logic

Step 1: Validating User Input and Executing Business Logic

Step one is Groovy validation on the input that is not relevant to the actual data movement and has been discussed in other articles. This also runs any business logic on the data that has been changed. The only difference between a Groovy and non-Groovy calculation is that the logic is isolated to execute on only the rows and columns that have changed. This has also been discussed in previous articles and is not relevant to the topic of real time synchronization.

Step 2a: Isolating The Edited Rows

Isolating the edited rows to synchronize is not required, but it will significantly reduce the amount of time the data map / smart push takes. If this step is skipped, hundreds, if not thousands, of products will be synchronized for no reason. This will certainly create performance problems where there doesn’t need to be. So, even though it isn’t required, it is HIGHLY recommended. This will be discussed at a high level. Much more detail on this topic can be read in Part 3 of this series.

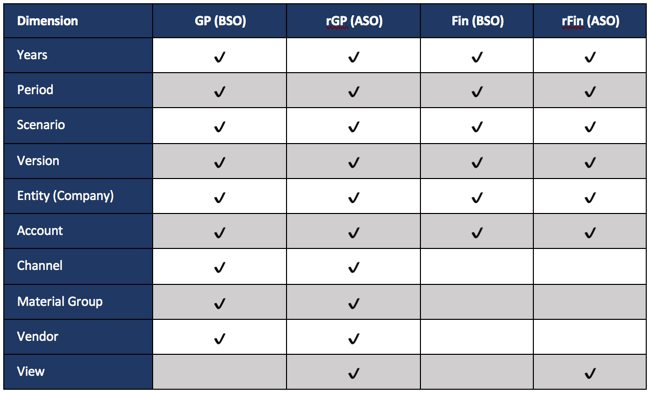

Although the POV in the GP form has dimensions that aren’t in Fin, Company is. This is the one parameter that is used all the way through this example. Year, Version, and Scenario are all fixed. The form is only for Budget updates. This is not common, so replicating this would likely require some additional variables to store Scenario and Year.

// Get POV

String sCompany = operation.grid.getCellWithMembers().getMemberName("Company")

def sMaterialGroup = operation.grid.getCellWithMembers().getMemberName("Material_Group")

String sChannel = operation.grid.getCellWithMembers().getMemberName("Channel")

//Get a collection of all the products that have been edited

def lstVendors = []

operation.grid.dataCellIterator({DataCell cell -> cell.edited}).each{

lstVendors.add(it.getMemberName("Vendor"))

}

//Convert the collection to a delimited string with quotes around the member names

String strVendors = """\"${lstVendors.unique().join('","')}\""""

Step 2b: Pushing The Changes To The GP Reporting Database

The next step of the process is to push the data (hopefully only the changed data) from the BSO database to the reporting database (GP to rGP in the diagram above). This step is basically pushing the same level of data from a BSO to an ASO database for the products that have changed. This can be done with a Smart Push or Data Map. It can also be done with a data grid builder, but this is a simpler way to accomplish it. A deep dive into the data grid builder is scheduled later in the series.

If you only want to further customize a push already on a form, then use a Smart Push. Otherwise, a Data map is required. There is a detailed explanation in Part 8 of the series and is worth reading.

Smart Push is used in this example. I prefer to use Data Maps but it is helpful to see both. A step later in the process will use a Data Map (push from Fin to rFin).

With this example, the Smart Push on the data form has all the appropriate overrides. The only thing needed to be customizes is the list of products that have been changed.

// Check to see if the data map is on the form and that at least one product was updated

if(operation.grid.hasSmartPush("GP_SmartPush") && lstVendors)

operation.grid.getSmartPush("GP_SmartPush").execute(["Vendor":strVendors,"Currency":'"USD","Local"'])

Why use a Smart Push or Data Map here? Could you use the grid builder? Absolutely. Quite honestly, I don’t know which is faster, but I am going to test this in a later post and compare the performance.

Step 3 & 4: Synchronizing With Fin and rFin

This is where new methods will be introduced, and honestly, the most complicated part. It is also the piece that completely changes the landscape and completes the circle on being able build real time reporting. Since data is moving from a BSO to an ASO, there isn’t a pre-built solution/method to do this. But, Groovy does open up the ability to simulate a retrieve, with a customized POV, and a submit. At a high level, that is what these steps accomplish. The POV from the form is used as a starting point and changed to a total vendor/channel/material group and retrieve the data from rGP (ASO so no consolidation is required), create another retrieve that is connected to the fin cube, copy the data at a total vendor/channel/material group from rGP to the fin cube grid, and submit it.

The following is Groovy Map, or Groovy Collection, that simply holds the translation between the accounts in the GP database and the accounts in the Fin database. This is nothing proprietary to PBCS or the PBCS libraries. If you are unfamiliar with these, explanations are easy to find by searching Google for “Groovy data maps.”

//set account map

def acctMap = ['Regular_Cases':'Regular_Cases',

'Net_Sales':'42001',

'Cost_of_Sales_without_Samples':'50001',

'Gallonage_Tax':'50015',

'Depletion_Allowance_Manual_Chargeback':'56010',

'Gain_Loss_Inv_Reval':'50010',

'Supplier_Commitments':'56055',

'Supplier_Spend_Non_Committed':'56300',

'Samples':'56092',

'GP_NDF':'56230',

'GP_BDF':'56200',

'GP_Contract_Amortization':'56205',

'Sample_Adjustment':'56090'

]

Now, let’s start in with the methods that have not been discussed in the Groovy Series. The remaining process simply copies the data at total channel, total material group, and total vendor, to the Fin databases to No Cost Center, which is void in GP.

If you are familiar with creating Planning Data Forms, or you use Smart View to create adhoc reports, you will understand the concepts of creating grids with Groovy. They include the page, column, and row definitions, all which have to be defined. Once they are defined, well, that is all there is . The script looks a little scary, but it is basically doing the things you do every day.

This first grid is our source grid. It will connect to the rGP (ASO) database and retrieve the data to be moved to the Fin and rFin databases.

// Create variables that will hold the connection information

Cube lookupCube = operation.application.getCube("rGP")

DataGridDefinitionBuilder builder = lookupCube.dataGridDefinitionBuilder()

// Define the POV for the grid

builder.addPov(['Years', 'Scenario', 'Currency', 'Version', 'Company','Channel','Material_Group','Source','Vendor','View'], [['&v_PlanYear'], ['OEP_Plan'], ['Local'], ['OEP_Working'], [sCompany],['Tot_Channel'],['Total_Material_Group'],['Tot_Source'],['Tot_Vendor'],['MTD']])

// Define the columns

builder.addColumn(['Period'], [ ['ILvl0Descendants("YearTotal")'] ])

// Loop through the Groovy Map for the accounts to retrieve

for ( e in acctMap ) {

builder.addRow(['Account'], [ [e.key] ])

}

// Initiate the grid

DataGridDefinition gridDefinition = builder.build()

// Load the data grid from the lookup cube

DataGrid dataGrid = lookupCube.loadGrid(gridDefinition, false)

// Store the source POV and rows to replicate in the destination grids (rFin and Fin)

def povmbrs = dataGrid.pov

def rowmbrs = dataGrid.rows

def colmbrs = dataGrid.columns

Now that the source is ready to go, creating the objects/grids that connect to the destination databases is next, which are Fin and rFin. It builds out the POV, columns, rows, and also loops through the cells in the source grid to get the data. Almost every line is duplicated, so don’t get confused. The reason is that the script is creating a grid to save to each of the fin databases. To make it easier to see this, the duplicate items are in a different color.

// Create variables that will hold the connection information

Cube finCube = operation.application.getCube("Fin")

Cube rfinCube = operation.application.getCube("rFin")

DataGridBuilder finGrid = finCube.dataGridBuilder("MM/DD/YYYY")

DataGridBuilder rfinGrid = rfinCube.dataGridBuilder("MM/DD/YYYY")

// Define the POV for the grid

finGrid.addPov('&v_PlanYear','OEP_Plan','Local','OEP_Working',sCompany,'No_Center','GP_Model')

rfinGrid.addPov('&v_PlanYear','OEP_Plan','Local','OEP_Working',sCompany,'No_Center','GP_Model','MTD')

// Get the column from the source grid and define the column headers for the grid

def colnames = colmbrs[0]*.essbaseMbrName

String scolmbrs = "'" + colnames.join("', '") + "'"

finGrid.addColumn(colmbrs[0]*.essbaseMbrName as String[])

rfinGrid.addColumn(colmbrs[0]*.essbaseMbrName as String[])

// Build the rows by looping through the rows on the source grid, converting the accounts,

// and inserting the values from rGP (source)

dataGrid.dataCellIterator('Jan').each{ it ->

def sAcct = "${acctMap.get(it.getMemberName('Account'))}"

def sValues = []

List addcells = new ArrayList()

colmbrs[0].each{cName ->

sValues.add(it.crossDimCell(cName.essbaseMbrName).data)

addcells << it.crossDimCell(cName.essbaseMbrName).data

}

finGrid.addRow([acctMap.get(it.getMemberName('Account'))],addcells)

rfinGrid.addRow([acctMap.get(it.getMemberName('Account'))],addcells)

}

If you noticed slightly different methods (dataGridBuilder vs DataGridDefinitionBuilder), you have a keen eye. Later discussions will go into detail on the differences, but the reason both are used in this example is because DataGridDefinitionBuilder allows the use of functions, like ILvl0Descendants, which was used so members were not hard coded.

The argument could be made that there is no reason to push the data to rFin since later in the process it will be replicated. I would not argue with that rational. However, for educational purposes, the push to rFin here will include USD and Local currency. The push later will only include USD. So, there is some replication that could be removed in a production application.

//Create a status object to hold the status of the operations

DataGridBuilder.Status status = new DataGridBuilder.Status()

DataGridBuilder.Status rstatus = new DataGridBuilder.Status()

//Initiate the grids connected to Fin and rFin with the status object

DataGrid grid = finGrid.build(status)

DataGrid rgrid = rfinGrid.build(rstatus)

// The print lines that send information to the log are not required,

// but showing the status is helpful in troubleshooting and monitoring

// performance

println("Total number of cells accepted: $status.numAcceptedCells")

println("Total number of cells rejected: $status.numRejectedCells")

println("First 100 rejected cells: $status.cellsRejected")

// Save/Submit the form to Fin

finCube.saveGrid(grid)

// Additional information sent to the log

println("Total number of cells accepted: $rstatus.numAcceptedCells")

println("Total number of cells rejected: $rstatus.numRejectedCells")

println("First 100 rejected cells: $rstatus.cellsRejected")

// Save/Submit the form to rFin

rfinCube.saveGrid(rgrid)

Step 5: Executing and Synchronizing Fin Logic

This is by far the simplest part of the entire process. This piece doesn’t have to be a Groovy calculation, honestly. In this situation, the Company can be grabbed from the form POV. That said, I like the ability to log things from a Groovy Calculation, so I have done so in this example. Why is currency calculated here and not in GP? Great question. Ah…this is just an example. This could be replaced with any logic.

This is the simple part...execute the business rules

String sCompany = operation.grid.getCellWithMembers().getMemberName("Company")

StringBuilder essCalc = StringBuilder.newInstance()

essCalc <<"""

FIX(&v_PlanYear,"OEP_Plan",$sCompany,"No_Center","GP_Model")

%Script(name:="FIN_Currency",application:="BreakFin",plantype:="Fin")

ENDFIX

"""

println essCalc

return essCalc

After any specific business logic is executed, the last step is to push the data to rFin. Rather than use a Smart Push like above, this time a Data Map will be used. My preference is to use Data Maps. Once the parameters are understood, I think it is easier just to pass all the overrides in a generic Data Map. Otherwise, the overrides are managed in multiple. I certainly can’t argue performance, simplicity, or other benefits for one method over another. It is completely a preference.

//Declare string variables to house POV members

String sCompany = '"' + operation.grid.pov.find{it.dimName =='Company'}.essbaseMbrName + '"'

//Execute datamap

operation.application.getDataMap("Fin Form Push").execute(["Company":sCompany,"Scenario":"OEP_Plan","Version":"OEP_Working","Years":"&v_BudYear","Source":"GP_Model","Currency":"USD","Account":'ILvl0Descendants("Account")',"Cost_Center":"No_Center"],true)

Performance

I have presented this concept 3 times to about 300 people. I always get this question.

OK, you change one product and it is fast. What happens if you change all of them?

To be completely transparent, pieces of this are not much faster, but the move from the detailed cube to the summary cube (GP to fin/rFin in this example) is lightning fast and makes no difference whether 1 or 30K products are changes. In a real world situation, planners don’t change every line every time.

Here is a summary of what I experienced. The first 4 are changes made at a lev0 of channel and material group. The second 4 are done at the top of those dimensions. The calculation of the business logic changes for obvious reasons. The push of the changed data changes for the same reason. It is simply a question of volume. The synchronization to the reporting consolidated cubes is not impacted. It doesn’t matter whether 1 or 30k products are changed because the data moving from the rGP cube is the same because it is pushing at a total.

* All times are in seconds

Conclusion

The reason I looked into Groovy was because of this example/client. The logic on the form was relatively complicated and included allocations, then based on the changes there were spreads through the months and additional adjustments to make sure impacts to revenue were impacted properly. The form save was taking minutes, and was unacceptable, for obvious reasons. The Smart Push was taking too long and had to be run in background, and would error due to size periodically. That gave me the idea of the push on save to the consolidated financial cube, and voila!

This introduces some incredible functionality that can change the landscape of what we can do with PBCS. Much of this has been discussed in previous pieces of this series, but the addition of moving consolidated data (without running a consolidation) throughout the applications is brand new. There are some more things to the script that could be done to even speed it up a little (only moving edited accounts and months, for example). In the near future, we will jump into this code at a more granular level and explain, line by line, what everything is doing. We will also optimize this example further. Look forward to that in the coming weeks. For now, a solid example is available for you to use.

What do you think?